The Political Atmosphere of the Halls

- Jul 6, 2017

- 8 min read

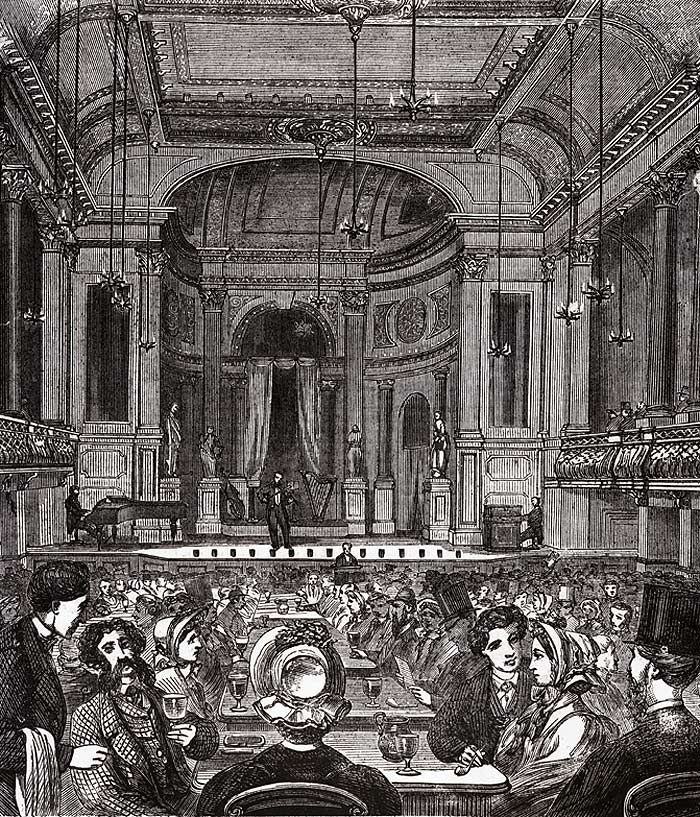

Traditionally, Victorian music halls have been presented by historians as conservative spaces. They cite as evidence, the loyalty to country, monarchy and empire shown in song lyrics, and the enthusiasm with which audiences sang along to jingoistic choruses. Indeed, all these qualities were present in Victorian music halls, and the overarching political tone was conservative. However, this tone was by no means entirely universal. Opposing opinions were present on the halls, and political loyalties varied depending on geography and audience dynamics. It is important to acknowledge these discrepancies, if we are to understand the complexity of working class political attitudes during the 19th century.

First and foremost, the music hall sector became increasingly conservative in the later decades of the 19th century because of the Liberal party’s attack on the alcohol trade; the lifeblood of the music hall business. The teetotal movement began to operate as a pressure group from the periphery of the liberal party, and in 1871, the Liberal Licensing Act, implemented by William Gladstone’s government, restricted the opening hours of public houses, regulated beer production and gave local boroughs the option to ban alcohol. The act was deeply unpopular and contributed to a conservative victory in the general election of 1874. Music hall proprietors saw these liberal policies as a direct attack upon their livelihood, and the audiences interpreted it as an attempt by the middle classes to control working class culture. This perception was enhanced by the attempts of temperance groups to implement programmes of rational recreation (entertainment for the sole purpose of education) in the halls.

Gladstone, as leader of the Liberal party from 1867, was the main target for frustrations. The music hall song, ‘The Politician’s Dream’ by N.G. Travers, portrays him as a hypocrite:

I’ll tell you how to be one day like our beloved Gladstone.

Make your speeches hyperbolic,

Take a dose of bile and ‘colic’,

Let your features be symbolic

Of what’s sage and sinister.

Get presented with some axes,

And pretend to cut down taxes,

Then you’ll be prime minister.

In defiance of the Liberal party and the middle classed backed temperance groups, an affiliation developed between the aristocrats and the working classes to ensure the survival of an alcohol trade free from government interference, and in defence of music hall culture. Consequently, the political loyalties of music hall properties and many of those who frequented the halls, belonged to the Conservative party.

Moreover, from the 1870s, the larger, commercialised West End music halls became popular with aristocrats, military officers, students and clerks, many of whom were traditional conservative supporters. The audiences of these establishments became increasingly pro-tory and so the songwriters, eager to impress, provided music hall stars with conservative material. The popular stars of the West End halls began to tour their repertoire of songs across the country, and so the songs designed for a conservative audience spread. A general pattern emerged; Conservatives were praised, while reformers were mocked.

The political hero of the halls was undoubtedly Benjamin Disraeli. After purchasing significant shares in the Suez Canal in 1875 for Britain to protect itself against potentially adverse trading policies in the region, he affectionally became known in music halls as ‘Dizzy’. A song written after the deal declared:

Ben Dizzy’s been busy. I’m told by a pal,

So keep it dark!

That he’s brought up both sides of the Suez Canal,

But keep it dark!

So if Russians should try to pass through,

He will say ‘Stop! this is England! Do what you may,

You’ll have to go round by a different way.

Music hall audiences admired his strong, imperial stance, and his popularity reached new heights in response to the anti-Russian policy he followed during the Great Eastern Crisis (1875-1878). Disraeli was so popular on the halls that just a mention of his name guaranteed applause. The Era stated in 1886 that ‘when in want of applause, play Lord Beaconsfield has been the motto of every tenth-rate singer of the last five years’. In the preceding year, they stated ‘the continual mention of Lord Beaconsfield, to the detriment of any other statesman, whether conservative or liberal, is becoming nauseating’. This is an exaggeration of the truth. Other politicians were mentioned, but no-one ever achieved the heroic status imparted upon Disraeli.

Joseph Chamberlain, as a liberal, had been mocked for most of his career in the halls. However, his treatment significantly improved when he split for the Liberal party in 1886 after disagreeing with the party’s support of Irish home rule. He was also later cheered in the halls for his involvement in formulating, as Secretary of State for Colonies, foreign policy during the Boer Wars. The halls were less kind to Charles Parnell, arguably one of the greatest reformist politicians of the 19th century. As a collective, music halls opposed Irish home rule and so, Charles Parnell, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party between 1882 and 1891, was frequently belittled. ‘Victoria’s School’ by Arthur Lloyd declares:

There’s a naughty boy in school and master Parnell is his name,

To Cause a great disturbance seemed to be his little game,

But one of the headmasters very quickly made him wince,

For master P. was shut up and he’s scarcely spoke since.

The Bolton Evening News on 24th December 1890 stated, ‘Parnell is now a first-class subject for music hall ridicule’ and that the ‘very moral audience finds food for excessive laughter in the details of the fire escape episode’. This referred to the song by G.H. Macdermott which referenced the allegations that Parnell had been involved in an adulterous affair:

Heavens! What a situation! Hardly time to put on one’s gloves! No chance to avoid detection, no way to save the lady’s reputation! Oh yes, thank goodness, there is one! Happy, thrice happy thought: The fire escape, the fire escape!

It was indeed a merry jape

When Charlie Parnell’s naughty shape

Went scooting down the fire escape!

In addition to political gossip and scandals, songs that emphasised patriotism, imperialism, nationalism, and xenophobia were popular on the halls, especially at times of war. The most famous of all was written in response to the Great Eastern Crisis, and introduced the term jingoism into the English language. The chorus of ‘We Don’t Want to Fight’ by G.H. McDermott boasted:

We don't want to fight but by Jingo if we do We've got the ships, we've got the men' we've got the money too We've fought the bear before, and while we're Britons true The Russians shall not have Constantinople.

Overall, the popular songs of the day demonstrated a pattern; conservative support, patriotism and a preference for the maintenance of the status quo. This is somewhat explained by the positive association between the Conservative party and the drink trade, and the increasingly aristocratic audiences of the West End halls. However, a large working-class liberal vote existed from 1867 until the First World War, and despite the West End halls being a melting pot of classes, across Britain, halls were largely frequented by the working classes, and yet, their liberal support appears diluted in the halls. But, as indicated earlier, conservative support was frequent in music halls, but by no means universal, and the presence of liberal support has largely been overlooked. Often the London centric view with which we reflect on music halls, causes us to overlook the anti-conservative sentiments that were present in the provinces.

Artists toured the country with their repertoire of popular songs, however, they often found that the audiences of provincial halls were less unified in their support for the conservatives, and often took an anti-heroic approach to war. Halls in Scotland and the north of England were far less enthusiastic about imperialism, and though London was more conservative than the rest of the country, pockets of liberal support remained within the capital. The political opinion of the crowd changed with geography, and accordingly, some artists adjusted the lyrics of their songs, or purposely chose songs that would be unproblematic for more liberal leaning audiences. G.H. Macdermott, when interviewed by the Pall Mall Gazette in 1886, stated:

‘You are quite mistaken in thinking that music halls are all conservative. My own experience, if it worth anything, teaches me that where you have a music hall in the centre of a conservative district you will as surely have a conservative audience. Take the case of the Pavilion. That is the centre of a great Conservative district…At the Pavilion, then, you get a distinctly Conservative audience. But take the other extreme. At the South London Gladstone is in a majority, and a Tory song is received with howls. The Paragon (Mile End) too, and the Cambridge (Shoreditch)’.

In response, the interviewer asked, ‘then Mr Gladstone is not so unpopular in the music halls as one would think?’, to which Macdermott replied ‘well, he may be now, after the Irish business, but in less momentous times not a bit of it‘. Moreover, the chairman of the Plough Variety Hall in Northampton declared in an interview with the Northampton Mercury in 1888 that in Northampton music halls, ‘as a rule the name of Liberals and Radicals go down remarkably well’.

Herbert Campbell alluded to the need of a music hall star to check the political loyalties of an audience before taking to the stage in his comic song, ‘What to Sing Nowadays’.

The best songs are political, the reason is, because

They’re easiest to sing, and always gain the most applause;

But just before commencing, you should always ascertain

The Politics of the Audience, and then you’re ‘right as rain’

For instance, if they’re ‘Tory’ you should sneer at William Glad,

And call him lots of nasty names, no names could be too hard.

Evidently, not all music hall audiences supported conservative ideals, and to avoid offending those with Liberal and Labourite leanings, songs needed to be carefully chosen. The songs of the halls may have been overwhelming conservative in nature, but one cannot assume that the audiences themselves were all deeply conservative.

Indeed, some music hall stars, instead of following the patriotic trend, questioned the futility of fighting for the British Empire and expressed anti-heroic sentiments. Herbert Campbell was famous for parodying the grotesque patriotism of his colleagues, and as Laurence Senelick sates, his song ‘I don’t want to fight’, ‘threw cold water on the very sentiments his audience had been bellowing and applauding moments before’. The chorus states:

I don't want to fight, I'll be slaughtered if I do I'll change my togs, I'll sell my kit, and pop my rifle too I don't like this war, I ain't a Briton true And I'd let the Russians have Constantinople.

A dramatic sketch by Charles Godfrey, entitled ‘On guard, a Tale of Balaclava’, highlighted the hypocrisy of halls calling for young men to do their honourable duty and enlist, for them only to be cruelly forgotten upon their return from war. The sketch followed the life of a Crimea veteran who had been left to die because of his country’s ingratitude. He requests a night’s lodging in a casual ward, only to be told ‘Be off, you tramp! You are not wanted here!’. The veteran replies ‘I am not wanted here. But at Balaclava- I was wanted there!’.

Moreover, ‘When they found I was a soldier’ by Joseph Tabrar suggests becoming a soldier was a way of losing one’s self.

When they found I was a soldier Sister Mary went right off her head; Father, he got drunk, mother did a bunk And the tom-cat fell down dead oh, Glory! Down came the lodgers with a rush, But they didn't stop there long; When they saw my sword, they exclaimed, 'Oh, lor! There's another good man gone wrong'

Such songs challenged the establishment, and Herbert Campbell’s song ‘They Ain’t No Class’, directly criticised parliament.

I ain't a bloke as rhands upon the lords Jist 'cos they've got a bit o' brass. For among the Upper Ten there are lots of gentlemen Though some on 'em ain't no class.

Though, it must also be acknowledged, that most individuals who visited music halls during the 19th century, did so with the expectation of being distracted from the hardships of their everyday lives, such as overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions. They did not want to be reminded of them during their leisure time, and so often, the presentation of politics on music hall stages was met with hostility from the audience. Sporting Life declared in June 1886, as part of a feature on the Great Macdermott, that ‘in Scotland the audiences won’t stand politics, so the Great Macdermott gives them none’. Moreover, music hall audiences frequently shouted ‘no politics’ when presented with overtly political performances.

However, when politics was acknowledged in songs and sketches, the overall tone across British music halls was that of conservatism. The establishment was rarely challenged and radical politics were never discussed. Ultimately, the Conservatives were the party that received the greatest amount of support from the halls, but there were discrepancies to this trend, particularly in provincial halls, and they must be acknowledged, rather than being ignored as an exception to the rule.

Comments